How a “universal, unifying experience” made Dartington dance

Despite its difficulties in recent years the Dartington estate outside Totnes retains its allure, combining beauty and momentous history. It was here 100 years ago that Dartington’s US-based benefactors Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst began their bold venture – both visionary and bizarre – to establish a ground-breaking centre in arts, industry and social life.

Steffi Andrews

A few years later they started Dartington Hall Trust to run an increasingly complex set of operations, spanning music appreciation to rearing chickens. Occupying a central slot in this mix was dance. Driven by the Elmhirsts’ broad set of aspirations, and boosted by Dorothy’s vast inherited wealth, a dance school was started on the estate in 1932. Housed in an impressive new building, Studio 6, it was run by Margaret Barr, part of an early wave of overseas-based dance practitioners which Dorothy and Leonard enticed to their Devon retreat.

The seeds from the Dartington tree are flourishing,

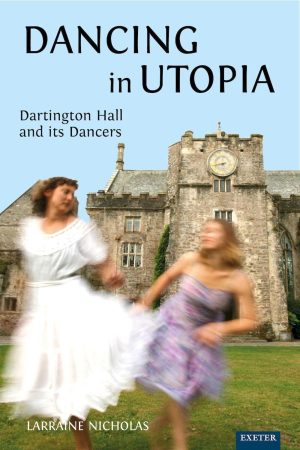

The story of how Dartington’s rich history has been interleaved with dance is set out in Dancing in Utopia, a meticulously researched book by dance historian Larraine Nicholas. “Dartington allowed a place for dance and that place became entwined with great themes – education, community, our planet and how our bodies form channels of communication to others,” Nicholas writes in an updated edition of the book, published to coincide with the centenary of the Elmhirsts’ establishment of Dartington in its modern form.

Nicholas is giving a talk in Dartington Hall on November 12 on how dance fits into both Dartington’s history and the wider world. In preparation for the first edition of her book, published in 2007, Nicholas made her first visit to Dartington in 2001. She was smitten. “Everything here is so beautiful, peaceful, gorgeous, blooming,” she wrote in her diary.

What made her write the book? Dartington could act, she thought, as a vehicle for a broader story. “I hoped …that a book focusing on one place within a long tract of time, would help to clarify the developments of dance in Britain. Themes that run through the book show evolving ways of understanding dance: as performance, education, and community participation.”

Nicholas became fascinated by the twin characters of the Elmhirsts, so different in many ways but united by a shared concept of what their “Dartington experiment” could offer. “Leonard and Dorothy were unusual for their time in valuing dance as an equivalent ‘high’ art,” Nicholas recounts. “I trace that to their own experiences, Leonard in India, and Dorothy in New York.” Leonard – not obviously an “arty” person and whose special gifts were regarded as being mainly about farming – was particularly captivated. “For Leonard, dance was a universal experience, organic in origin and unifying,” she writes.

Her book homes in on the breadth of dance experts – including Louise Soelberg, Sigurd Leeder and Mark Tobey – who were attracted to Dartington and whose ideas evolved while there. The vignettes include how Barr had to bribe a schoolboy Michael Young into appearing on stage in one of the estate’s earliest dance performances. The later Lord Young was among the first pupils at Dartington’s “progressive” school. He went on to become one the UK’s great social innovators, as well as probably Dartington’s biggest advocate in the wider world.

Nicholas details some of the conflicts that have punctuated Dartington’s history. Occasionally they impinged on dance. In one instance, Barr was sacrificed after the celebrated German dancer and choreographer Kurt Jooss and a team of colleagues, in a potentially perilous position in Essen as Hitler grabbed power, was recruited to Dartington in 1933.

With the Elmhirsts star-struck by the possibilities afforded by this top name, their German refugee Jooss was granted top billing leaving Barr – who had come to Devon from the US – to find a challenge elsewhere. The broader aspects to Dartington’s history – including the rise and fall of the estate’s key institutions in the shape of the school, Dartington College of Art and most recently Schumacher College – are woven into the narrative.

As part of the changes to how Dartington is run, pushed through from 2023 by the Dartington trust’s new chair Lord Triesman and a team of restructuring specialists, Studio 6 has been let out to a leisure firm which uses it as a gym. The gym appears well regarded. While space there can be let out to Dartington dance customers, dance at Dartington is in far from good shape, as Nicholas acknowledges.

In what might have been regarded as one of the few positive developments for Dartington dance in recent years, the Dartington trust in 2019 recruited as a trustee a notable dance expert, Emma Gladstone. Covid-19 struck soon afterwards. Its consequences disrupted any plans Gladstone might have had. Amidst the upheavals following Triesman’s 2023 actions, and already unwell, Gladstone resigned in October of that year and died soon afterwards.

This run of developments at Dartington fits in with the broader picture. Dance education in the UK has been downgraded in recent years, suffering especially from public spending cuts. But in her book Nicholas resists sounding downbeat. She lists the dance practitioners who have spent time at Dartington and who are using their experiences to good effect elsewhere.

“The seeds from the Dartington tree are flourishing,” she writes. Dartington has given dancers and people associated with dance “a core of knowledge that could be enhanced in … individual ways into remarkably different creativities”.

The rhythms and poetry from Dartington dance live on.

Top Feature image: Epithalamium performance in the Dance School 1933.photo: Dartington Hall Trust